Encourage Innovation & Secure Buy-In with a Balanced Portfolio of Experiments

Buckle up, and hold onto your curiosity hats, folks, because we’re about to plunge into the world of A/B testing portfolios like never before!

We’ll start by breaking down multiple concepts and clearing up a few myths and misconceptions, and then we’ll dive into the meat (or tofu for our vegetarian friends) and potatoes of creating a balanced portfolio of experiments for your conversion rate optimization (CRO) programs.

Now, if you’re anti-potatoes or you’re already an A/B testing whizz riding the bullet train of innovation, feel free to skip the introductory sections and hop on directly to the juicy bits (Click here ).

However, if you own a “CRO” program, or if your agency/business runs experiments, and yet, you’re facing these four all-too-familiar signs of stagnation, stick around, my friend. Read it all.

- You used to see big lift numbers in the early days. But now, most tests “lose”.

- The HiPPO feels their professional experience can do so much better!

- You heard whispers of the CMO cutting your budget and allocating it to PPC.

- You were supposed to hit a $1.5M in revenue increase, but that number was well short of your enthusiastic and proud projections.

There might be 3 things wrong with the way your testing program is set up:

- You test to improve a metric.

This is problematic. If metric uplifts are the sole purpose of running a test, rest assured that the smart folks in your team will find a way to move the number.

For example, if the aim of your experiment is to get more people to add items to the cart, testing a cadence of increasingly jaw-dropping discounts is an easy way to drum up action and interest. But what happens when they are privy to the (yet undisclosed) shipping cost? Or when the discount is designed to move the needle for the prospective customer (get them to add a product) but completely breaks your unit economics and your acquisition cost?

Also, adding to cart isn’t a guarantee of purchase. If the actual checkout process hasn’t been analyzed for roadblocks customers face, the metric you were aiming to improve (and did in fact improve) comes to naught.

Yes, you can turn your attention to more downstream and definitive metrics like transactions completed.

However,

- (i) Go too downstream and you are caught up in working on levers that do not create change, and are stuck with trying to budge outcomes like “profit”.

- (ii) And the problem of perverse incentives sticks around. Let’s go back to our original example. This time you want to improve the transactions completed. You again opt for steep discounting. You’re savvier now, so you go ahead and also optimize the actual checkout process. YES! It works. But, the CAC is prohibitive. Plus, you did not solve the actual problem — a lack of genuine desire for the product because of poor Product-Market fit or vague messaging.

You had discounts as a proxy for laying a solid and lasting foundation for your business. Yikes…

Tests said you were winning. In reality, you were not.

- You set performance marketing expectations.

Simon Girardin of Conversion Advocates explains it so well that we’ll let him hammer home the point.

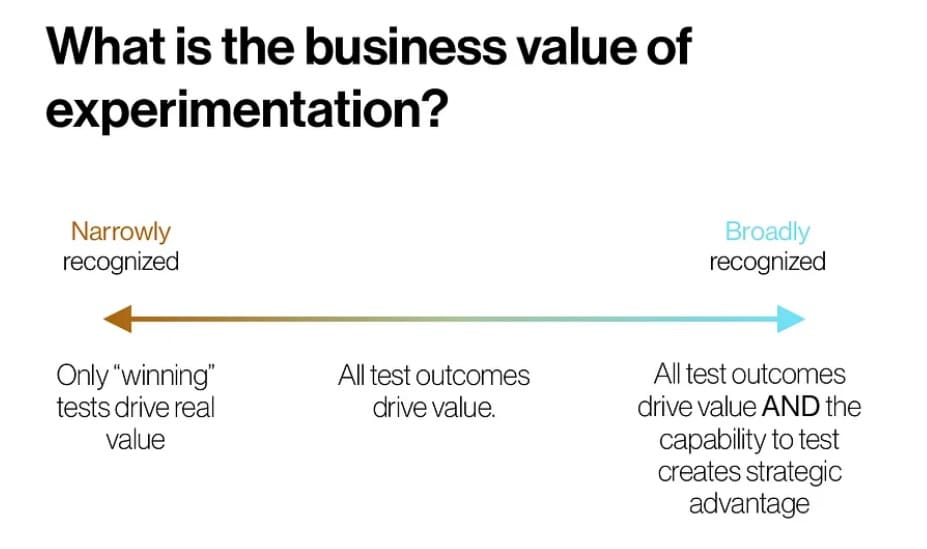

TL;DR: The ROI of experiments is important. But don’t think of experimentation as “number in, number out”.

You aren’t experimenting just to get more leads or to improve only your revenue-centric KPIs.

The biggest advantage of experimentation lies in the fact that it lets you understand how your prospective buyers perceive and interact with your business; how certain levers and the nuts and bolts of motivation impact them given the unique mix of your product, pricing, and differentiator.

The fact that experiments amplify your existing business results while unearthing the true nature of consumer desire in the context of your brand is the cherry on top!

If you want to go a layer deeper, look at what Jeremy Epperson thinks about the role experiments play in shaping your culture and business.

It touches everything — from fostering a fearless culture of letting data do the talking to placing customers and their problems at the heart of business endeavors.

If you’ve paid for it, allow experimentation to showcase its full range of benefits. Don’t sell it short. Please.

- You ignore the solution spectrum.

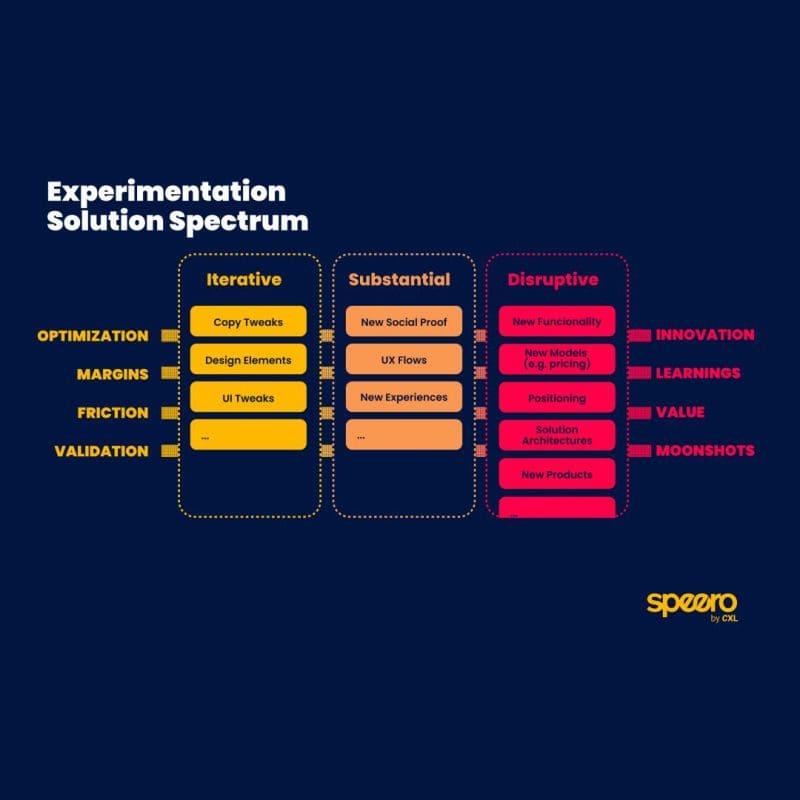

Solution Spectrum is a term popularized by Speero. They’ve even created a blueprint to go with it.

This one is the culmination of the issues discussed above.

When you choose tests to execute, you rely on a prioritization framework. Based on years of research, and speaking to some of the best minds in the space, we know prioritization is difficult to get right.

An oft-overlooked factor in conventional experimentation prioritization is prioritization based on the nature of the solution that’s being proposed through the tests.

- Are you optimizing small elements in the hope of stumbling upon a big impact? (This kind of testing can be the result of blindly following best practices, cursorily glancing at quantitative data, or copying tests from competitors.)

- Are you testing bigger changes but the scope of the result is still narrowly tied to conversion rate uplifts?

(This kind of testing may be fed by multiple data sources but clings to the idea that experimentation is a tactical channel only.)

- Or are you being an intrepid explorer? Are you embracing disruption in your solutions to bring innovation to your business?

(Programs that dare venture here are programs that realize the strategic value of experimentation. They aren’t necessarily the biggest and most funded endeavors. They are definitely the most aware, though; the ones that see experimentation in business as a reflection of experimentation in life — the chance to learn how causation works so the link can be leveraged moving forward!)

Experimentation is Human Nature™: The True Business Value of Running Experiments

“Experimentation is human nature.”

You observe a set of events, you suspect a causal link, you hypothesize why this link exists, and then you take action.

You re-execute the independent event and you look for the replication of the dependent event.

This cycle is ubiquitous. And in humans, it takes mere seconds to run its course.

We don’t acknowledge it often, but in everything we do—from identifying that we are allergic to a food group to cutting out distractions that seem to hamper our quality of sleep to understanding our partner’s love language—we run rough and ready experiments every day.

We can go so far as to say all human progress can be traced back to curiosity and experimentation. We are curious about meaning and purpose. And this compels us to understand why things happen the way they do.

Then why does experimentation take on such a heavy tone when it comes to the business world?

Well, there are risks associated with running experiments. When looking for that rogue eatable that gives you IBS, you accept the risk of spending an unpleasant afternoon in the loo (if you’ve correctly identified what brings on the scourge).

A business has higher stakes. Experimenting on established channels can upset profit.

No one wants that.

Then there are costs to running the experiments — people, tools, processes. If Convert’s data is anything to go by, only 1 in 7 experiments shows a significant lift.

When testing to move the needle on a metric, that’s seriously bad news.

This is where a seismic perspective shift is required.

All experiments are valuable: the ones that win help you learn what impacts behavior. The ones that lose help you learn what doesn’t influence your customers so you can stop wasting budget on items. And flat or inconclusive experiments tell you to re-think the scope of the change (maybe what you introduced didn’t elicit a strong enough response) and your execution.

Freedom from Wins Only = Balanced Portfolio

Yes, like the ever-elusive happiness, not chasing wins gets you the biggest experimentation wins.

‘Cause you realize that the objective is to get as close to experimenting in different ways as possible:

- On different channels

- With different types of hypotheses

- Based on past learning

- Based on blue sky thinking

- Based on existing frameworks

- And so much more!

Two concepts come in handy here:

- The idea of a portfolio. We are borrowing liberally from John Ostrowski, Director of Product & Experimentation at Wisepublishing.

Diversification covers more ground. It safeguards your assets (your business’ ability to constantly stay ahead of the competition and bring products and experiences your buyers crave). - The Explore vs Exploit balance that guides how you manage your experimentation portfolio.

In the experimentation world, it is common to hear the differentiation between “explore ” and “exploit ” experiments.

For me, given that I’m a bit of a sucker for semantics, there are two valid interpretations.

The first interpretation finds the difference between “exploiting” and “exploring” somewhat akin to that of “CRO” vs “Experimentation”: the former is about optimising, a.k.a. getting more juice out of a product or process; the latter is more expansive in that experiments can be simply used to learn something we don’t know, without the express need to extract any additional (read $$$) juice.

Exploitation is about making decisions, whereas exploration is about learning new things.

The second interpretation, possibly much more commonly referred to, is the one that differentiates “exploitation” and “exploration” in terms of risk.

From this point of view, exploitation is about taking calculated risks, using data that we believe to be true given our observations so far. It is about obtaining marginal gains, critical for any business.

Exploration, on the other hand, is about taking big leaps to discover the unknown. With big risks, big rewards… and big failures.

Exploration is where new, groundbreaking ideas come from. Needle-moving changes that give us an edge over the competition.

Put simply, exploitation is about continuing to do what we do, but better and faster, whereas exploration is about fundamentally changing what we do.

Regardless of which of the interpretations one prefers, a good experimentation program is one that combines both because experimentation is both learning and decisions and managing risk.

Using the first interpretation, having a healthy balance of wins and learnings is important. A company needs to make money to remain in business, but it also needs to understand its customers to better serve them and stay current in an increasingly competitive world.

While we in the business of experimentation would likely argue that the main role of experimentation is to provide learning, very few of us can deny that bill-payers want ROI. If we want to keep learning, we must ensure that ROI keeps us in business.

From the second angle, just like managing an investment portfolio, managing an experimentation program is about finding the right balance between “safe bets” with small but steady returns and “big bets” for a chance to win big.

If we invest all our resources in exploitation, bolder competitors will eventually overtake us. Conversely, if we invest all our resources in a handful of exploratory big-bets, given that about 8 in 10 business ideas fail, we risk losing it all with a bad hand.

It is also about resources. Incremental changes are often faster and easier to deliver so they can keep our pipeline always full. However, it can also clog the system with so many small changes to make, not leaving space for needle-moving changes.

Explorative changes are often big pieces that need more resources and time, so if all our focus is on these, we will miss many opportunities in the meantime.

As Ruben de Boer would put it “success = chance x frequency”

So if we are not maximising frequency, we are missing half of the equation.”

David Sanchez del Real, Head of Optimisation, AWA digital

David and the AWA team have further elaborated on the subject of exploring possibilities versus exploiting opportunities through experimentation. Read the blog here.

Sidenote: Diversity Encourages Balance

When you bat for diversity in the details, the bigger picture is more balanced and better performing.

For example, if you create content with fresh faces, you see richer blogs, get more SEO cred, and earn way better distribution.

The truth of this analogy applies to experimentation.

For a balanced portfolio of tests that prioritizes the right outcomes (not just wins), you must experiment with the types of tests to execute.

In a mammoth piece for Convert, everyone’s favorite eloquent experimenter Alex Birkett talks about 15 different types of tests and where to run them.

At a glance, they are:

- A/B tests

- A/B/n tests

- Multivariate tests

- Targeting tests

- Multiarm Bandit (MABs)

- Evolutionary algorithms

- Split page path tests

- Existence tests

- Painted door tests

- Discovery tests

- Innovative tests

- Non-inferiority tests

- Feature flags

- Quasi experiments

Some tests are categorized on the basis of the number of variants served or how and where the variants are served.

Other tests are categorized on the basis of the type of insight they validate and activate.

Let’s throw Jakub Linowski’s perspective in the mix. He has a rather interesting way of thinking about the “type” of tests to run in your goal to achieve a balanced portfolio.

And don’t worry, all ideas and every bit of research don’t need to come from you or a single strategist.

Take a look at chip economy and betting to prioritize. Someone experimented with them and found that the poker face of data is all that more valuable when ideas flow from different team members.

How 10 Veteran Testers Create Balanced Experiment Portfolios

Moving from the realm of high-level advice to take a peek at how industry veterans work to create a balanced portfolio of bets (experiments) that can:

- Build faith in the program

- Steadily work towards the org’s 5-year vision, and

- Bring a healthy mix of exploration and exploitation to the table.

The sentiment that came through, again and again, is “paying for itself”.

The best in the space understand that learning is great and is the real prize. But to pitch it as the prize, the C-suite should see experimentation as a tangible strategic advantage in the quest to hit real revenue numbers.

Failing to do so endangers buy-in.

Struggling to secure buy-in? Alex Birkett wrote a fantastic piece detailing 13 tried-and-tested ways to position experimentation as a winning strategy.

Introduce Stakeholders to Revenue and Non-Revenue Experiments

David from AWA digital talks at length about alignment and understanding.

Align yourself with your client’s or your organization’s interests. Understand what the biggest problems are, so you can uncover solutions by running experiments.

It’s also essential that you allocate resources upfront to revenue-generating and innovation-seeking tests, and set the right expectations for both.

Each professional interviewed for this article has their way of tagging and categorizing tests (based on their overarching end goal or theme).

David’s take includes tests run to support the product roadmap, tests run to optimize what is already working, and tests run to validate decisions that have already been made.

This last category is overlooked, but as Jonny Longden suggested in this LinkedIn post, it is often easier to communicate the value of experimentation by putting the spotlight on the dollars it can save right away.

What I can say off the cuff is that one of the ways in which we make these decisions is by working very closely with our clients.

While every client is different in how they organise and make decisions, our goal as consultants is to engage at a strategic level with decision-makers.

We work hard at understanding their business, their sector and their challenges, and we support them in solving them through experimentation.

For example, we have a client that has established products that they’ve been selling for years. These continue to be their main revenue drivers but consumers are changing, which requires adaptation if we want to avoid going the way of Polaroid or Nokia.

To this end, we support them by testing new services, their value proposition, market acceptance, etc. These won’t bring immediate revenue, but gathering the right data for these strategic decisions is business-critical.

While we help them solve these larger business questions, we keep our eyes on the ball by constantly improving the experience across the consolidated products and services, making sure that the programme pays for itself with plenty to spare.

We have agreed targets in terms of velocity and ROI.

Velocity targets include “Revenue” experiments and “Non-revenue” experiments so that we can ring-fence some of the effort for these crucial activities, and the ROI calculation excludes these as they don’t necessarily have a direct monetary value yet.

One of my best pieces of advice is to reach an agreement on what level of support each stream will receive so that resources can be ring-fenced accordingly (with flexibility) before things start to get muddy.

John Ostrowski and Andrea Corvi and I worked on what we called “The experimentation framework”, which made us runners-up for the Experimentation Culture Awards, 2021. The framework divided all experimentation initiatives within the business as:

- “Product initiatives”: supporting decisions that product teams were making, some big and some small, with experimentation

- “CRO” experiments: fast, agile and mostly small improvements aimed solely at squeezing as much juice as possible from our existing experiences

- “Safety net”: experiments aimed at measuring the value of decisions made without prior testing”

This framework helped us gain alignment with stakeholders at different levels and agree on better resource allocation and prioritisation. Whether you use ours, adapt it or create your own to suit your company, my advice is to agree on a shared framework to help you do the same.

David Sanchez del Real, Head of Optimisation at AWA Digital

Validation Keeps Your Program Afloat

Kelly Anne Wortham is the founder and moderator of the Test & Learn Community (TLC).

According to her, building the right portfolio embeds experimentation in the decision-making process.

You bring innovation and revenue through optimization and personalization, but at the same time, you also validate decisions through testing. You celebrate the saves as much as the wins.

If you prove beyond the shadow of a doubt that most decisions taken on the fly don’t work (and even cause harm) and tests can identify what to roll back, then you guarantee a budget for experimentation.

Businesses will never stop taking decisions, even if they momentarily pause the sweep for innovation.

Here are two basic categories within testing: optimization and validation. Within optimization falls CRO, personalization, and all other experimentation designed for improving the user experience.

Within validation, I’m including all feature flagging and A/B tests designed to validate decisions including back testing, front door tests, and rapid experiments.

From my perspective, a balanced portfolio is one that is balanced between exploration and exploitation. That is to say between focusing on optimization and validation.

Validation ensures that you are balancing the saves with the innovation. Innovation is crucial for growth. But the saves are what provide the security and the funding for that foundation for growth.

If you focused all of your time on optimization efforts (CRO, etc), you could miss learning that an expensive new feature is going to be developed elsewhere that your team could have helped prevent and saved the company millions of dollars.

Those saves really help with the ROI story. We celebrate wins, but we should really be celebrating the saves.

A balanced portfolio between optimization and validation, between innovation and risk mitigation allows you to support the full marketing and product side of your business. It engages the entire organization and ensures that experimentation becomes a part of how decisions are made going forward.

Kelly Anne Wortham, Founder and Moderator of the Test & Learn Community (TLC)

Diversify the Portfolio with the Levers Frameworks

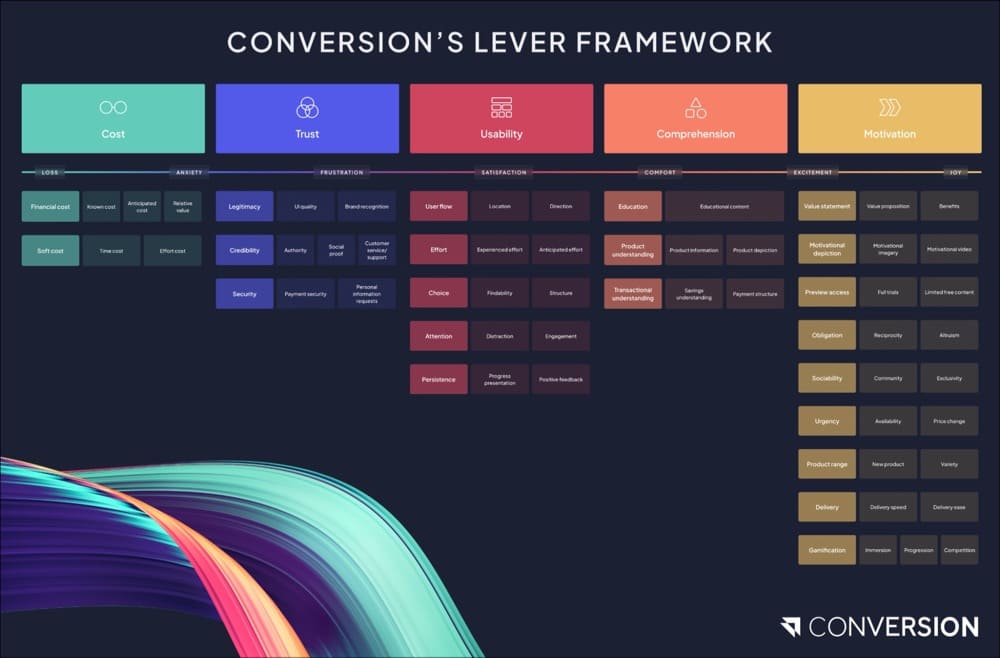

According to Conversion.com, a lever is any feature of the user experience that influences user behavior.

In fact, Conversion.com has gone on to identify 5 master levers of persuasion.

- Cost

- Trust

- Usability

- Comprehension

- Motivation

The master levers then break down into different levers and sub-levers, allowing you to categorize your user experience changes at three levels of generality.

Another blueprint you just can’t miss!

We spoke to both Saskia Cook and Steph Le Prevost at Conversion.com.

While Saskia focused on the categories she uses to diversify client portfolios, Steph shared how these categories work together in hands-on execution.

Interestingly, Steph also talked about the concept of earn (revenue) and learn (non-revenue) experiments and the vital role played by validation in facilitating better decisions.

You might have plenty of experiments that score high in terms of prioritisation on an individual level – but considering the diversity of your portfolio helps you evaluate your strategy more holistically. This will help you avoid running too many experiments on the same lever, or too many low risk experiments. Ultimately you will run a more successful strategy as a result.

At Conversion[.com], on behalf of each client, we balance their portfolio of experiments through a number of tried and tested frameworks:

- The Lever Framework

We categorise all of our data, insights & experiments by lever. This means we can prioritise running experiments on the most high potential levers – identified by research – while ensuring we are testing across a diverse range of levers (i.e. not putting all our eggs in one basket).

At Conversion, we also keep track of which levers we are exploring vs which we are exploiting.

It’s valuable to ensure your program has a mixture of explore & exploit experiments, to double down on success while keeping an eye on innovation & making new discoveries.

- Risk Profile

Every experiment you run is low risk, high risk, or somewhere in between. At Conversion, we categorise all our experiments by risk level. We then actively manage that balance in response to our client’s industry, season, and so on. If you’re not consciously managing your program’s risk profile, you’re probably not getting the full benefit of experimentation. Learn about our risk profile approach here.

- Diversifying your executions

Often there are multiple options for executing an idea. One important factor in deciding the best execution is to consider whether it will improve the diversification of your experiment portfolio. At Conversion, our designers categorise our experiments by what specific changes were made – was it copy? Imagery? Below the fold? On an interstitial? This way we can ensure we are diversifying at this more granular ‘execution’ level too.

Similarly, our Consultants consider if any psychological principles are at play within the experiment. We tag each experiment accordingly, using the categorisation promoted in the book Smart Persuasion by Philippe Aimé & Jochen Grünbeck.

- Diversifying at a ‘goal’ level

At Conversion we recommend you don’t just apply experimentation for CRO alone. Apply it for product discovery & expansion. See article that expands on this here. Many companies think of experimentation too narrowly (or too short term). Therefore they limit themselves to only certain types of experiments with a narrow objective.

Part of this is getting the balance right in terms of earning & learning experiments. I.e. A painted door experiment won’t immediately earn you anything but you can learn vital information to inform your product strategy that will help you earn more in the long term.

Similarly, consider how much more of an impact you could make if you expanded experimentation across more of your business KPIs. E.g. is there value in testing to optimise retention, not just acquisition?

Saskia Cook, Head of Experimentation Strategy at Conversion.com

We use the explore, exploit, fold methodology when it comes to levers (this refers to any feature of the user experience that influences behavior).

What this means is that when we onboard a client we conduct an explorative study, and take in any internal information about past experiments or their users.

We’ll use our lever framework to tag up these insights, and then using the master levers, cost, trust, comprehension, usability and motivation we can start to see where the barriers and motivations lie.

We’ll cast the net wide at the start, exploring the levers we can, and then as we get winners we will exploit. With iterations and new applications of the lever.

If we consistently see flat or negative results (depending on the insights we have) we may then choose to fold the lever.

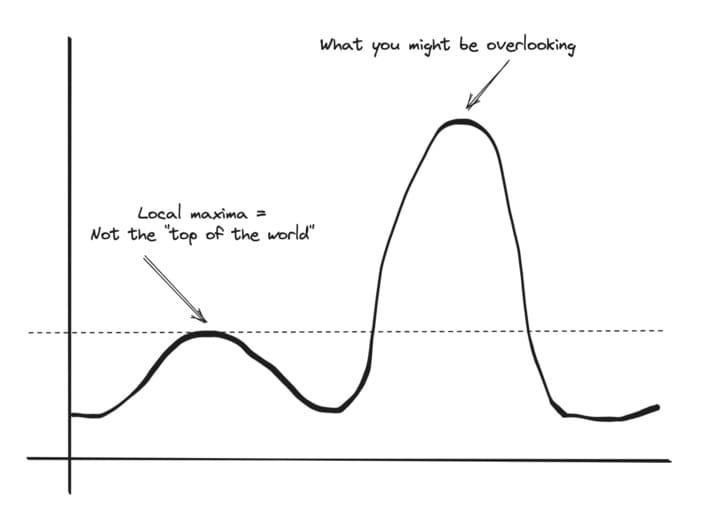

Striking the balance is difficult as there are so many things to explore when experimenting but using the lever framework coupled with research allows you to find the starting point. Coupling this with a risk profile works wonders, as you can start to build out a picture of where the website is on the local VS global maxima scale and then push your concepts further to achieve your goal.

All of this needs to play a key role in prioritisation, having a good framework which takes into account the insights, the confidence of the lever (exploit, explore) and the risk profiles helps – but you need to also look at dependencies and know your client well.

Setting the goal together early on allows for much easier conversations when some experiments do not ladder up to the revenue goal. In this case you can balance your earn and learn experiments, earn ladder up to the goal, learn help you go beyond ROI from experiments, and help the business truly see value in the experimentation mindset and way of working.

You can help test new products and features and reduce the risk or inform product roadmaps.

Steph Le Prevost, CRO Consultant at Conversion.com

This section is generously contributed by Gabriela Florea, CRO Manager at Verifone.

Her perspective is unique because Verifone is a FinTech leader providing end-to-end payment and commerce solutions to the world’s best-known retail brands.

Verifone’s CRO team works directly with clients, testing changes to their checkouts and helping them grow with the payment processor.

In our line of business, the clients we work with usually expect a win when they run an A/B test with us and – of course – revenue growth. The bigger the increase, the better. With this in mind, I’d say the bigger chunk of our experiments focus on testing hypotheses that already proved to be winners with other clients because it’s the easiest recipe for success & the one that requires little risk management.

Doing so doesn’t guarantee a win, but it has a bigger chance of turning into one. And while this tactic helps us stay on track and achieve our KPIs, we do make room for other types of experiments and for learning from them, for sure.

Lately, we have invested time and effort into generating new hypotheses, even if it’s a bit riskier to approach clients with ideas that have not been tested before. If you’re not working with a client that only wants a one hit wonder A/B test, there will always be openness to innovation, to new testing ideas and to learning from both wins and losses.

In terms of how we balance our successful testing hypotheses versus new & untested ones, I’d say each test allows for learning – it’s a matter of time & how we prioritize this aspect as we roll them out.

If we’re testing a new shopping cart template, the learning aspect will definitely take priority. And it’s only natural to be more curious when something fresh is being tested for the first time rather than when you have recycled the same hypothesis across different clients.

I think the balance between ‘testing to optimize’ and ‘testing to learn’ varies and gets dictated by your prioritization framework and your pipeline of tests. When you have a big number of clients waiting for you to deliver tests and help them grow their revenue, I believe it’s fair to say learning takes a backseat. However, if you’re lucky and have an extended CRO team, then learning gets to be in the driver’s seat more often than not.

Most of our tests are done for optimization. We cover 3 types of experimentation: bake-offs, A/B tests and split tests. The bake-offs are usually the ones used for validation.

We either validate that we are performing better than a competitor for conversion rates and RPV and the client stays with us or we validate that we are performing better than their current payment processor and the client can then decide to switch to processing their online orders with us.

Apart from this, our experimentation is done with the main purpose of optimizing our clients’ shopping carts, either by increasing their CR or their RPV. We can optimize the current shopping cart a client has, we can suggest testing a new template for their shopping cart, we can also suggest testing our new platform named ConvertPlus versus Legacy. Currently,

Legacy holds 83% of our sales volumes and we are encouraging our clients to check out the new shopping carts available on ConvertPlus, such as the one step inline cart.

In terms of balance, we are working on a 1-3-3-3 ratio and by what I mean bake-offs stand for 10% of our workload, and the other 90% are equally split among:

- A/B testing for changes on a client’s current shopping cart (optimizing it, basically)

- A/B testing a new shopping cart template (either we create a totally new shopping cart template for the client and test it as a variation OR we use as a variation a different shopping cart template that was previously tested & won with past/other clients)

A/B testing a different shopping cart template (such as the one-step InLine cart, which is a different technology and a different type of a shopping cart, suitable for what we call fast shopping)

Fold the Lever or the Roadmap!

If you run an experimentation program, get comfortable with walking away and often even binning your efforts.

In the previous section, Steph referred to “folding levers”.

Now we have Gintare Forshaw with her experience around folding an entire portfolio of experiments!

We love a contrarian opinion.

Having worked with various-sized businesses, I think that the concept of balanced portfolio doesn’t always exist as such.

There are so many factors that will determine how the experimentation program will be run and sometimes it needs an overhaul too. For example, one of my clients needed an overhaul of their whole roadmap because they shifted their acquisition model and with that the audience has changed too, so the focus that was there 6 months ago wasn’t necessarily valid anymore.

Don’t be scared of the overhaul, it doesn’t mean failure, it might mean more successful and impactful future tests and strategic implementations.

This all goes back to being agile, adapting to ever-changing business needs and priorities, not chasing the biggest % of experiments that were run or other metrics but understanding that sometimes making a shift will reduce the risk of poor experiments and increase the opportunities for further experimentation.

Gintare Forshaw, Co-Founder of Convertex Digital

Do Your Best to Avoid Bias

Many in the experimentation community go HiPPO hunting. And while the memes are cute, the highest-paid person—or for that matter of fact any stakeholder—can have ideas worth testing.

It is essential to avoid bias, either way, and labeling or categorizing tests to account for this can save the day.

Next up we have Max Bradley with the idea of proactive and reactive tests.

Typically an experimentation program will have a mixture of proactive and reactive tests on their roadmap. Proactive experiments are those that have been initiated from within the team whereas reactive are experiments that have come as a result of a stakeholder request.

It is important to judge all ideas equally in terms of prioritisation, scoring potential experiments fairly and avoiding bias towards internal ideas.

I like to mix large and small experiments in a roadmap, this I have found is a strong way to manage and maximise resources. It has an additional benefit of spreading risk, avoiding having “all your eggs” in a large experiments that costs a lot of time and money to run.

I ask everyone involved to consider whether we can reduce the scope of an experiment to validate the proposed concept as a first step. The majority of experiments in a mature program will “lose” so it is important to be as efficient as possible.

Validating the potential value of an experiment during the prioritisation phase is crucial also, time and resources are limited so you want to ensure you are targeting things that you believe will drive noticeable value.

The important thing is to have an overarching end goal or theme you are trying to achieve. There will be multiple ways to get there but having that in mind will ensure the roadmap is focused on driving value to the business.

Max Bradley, Senior Product Manager at Zendesk

Design Categories and Pick Valuable Tests

How do you do that?

Our next set of experts shares their best tips.

Haley Carpenter uses pre-test calculations, prioritization, and resource allocation to pick valuable tests.

Choosing experiments should be a data-driven process. It should be based primarily on pre-test calculations, user research, and a prioritization framework.

You need to know the viable testing lanes, determined by MDEs and duration estimates. Cut all of the ones with MDEs higher than 15% or estimated durations that are longer than eight weeks.

User research includes methodologies like polls, surveys, user testing, card sorting, tree testing, heatmaps, session recordings, analytics analysis, and interviews. The more ways you can back up an insight, the more confident you can be in your test idea. Logic behind a test idea shouldn’t frequently start with “we think,” “we feel,” or “we believe.” If you don’t do any research right now and don’t have the know-how or resources, start with one methodology and branch out from there. It doesn’t have to be overwhelming. (Know that analytics is table stakes these days, so I don’t really count that anymore.)

Prioritization frameworks are vital. I don’t care what is used as much as care that you just have one. There are many out there: PIE, ICE, PILL, PXL, etc. I like the PXL. Pick one that you can customize and scale.

Once you have the lists of tests you’re planning to run, put them into a roadmap in the form on a Gantt chart. Map out your months in advance.

On a related note, you should aim for balance in your roadmap. Mix tactical and strategic, large and small, simple and complex, precision-focused vs. learning-focused, so on and so forth. Tagging your tests in these ways is helpful to keep a pulse on this.

Lastly, have an idea submission form. That way, people can still feel involved but eventually become less inclined to try and shove things into your roadmap (if that’s currently a problem for you). Having proper processes and systems are the underlying backbones for all of this.

Haley Carpenter, Founder of Chirpy

Danielle Schwolow believes in a prioritized Airtable that takes into account factors such as test vs implement decisions (based on heuristic analysis), and weight given to what is a priority for the leadership team.

I’ve found that one of the biggest challenges we face as optimizers is the opportunity cost of testing vs. implementing best practices.

To make strategic decisions on when to test vs implement I rely on a prioritized Airtable that has two categories one for testing and one for implementation. I use a simplified version of CXL’s PXL questions and a Heuristics/Best Practices Audit inspired by the Baymard Institute to review a website. I’ve added a column of “priority for leadership” to be included in the logic for prioritization.

The Best Practices Audit will identify what should be tested vs. what should be implemented.

This is all plugged into an Airtable and prioritized based on a simplified version of CXL’s PXL.

I then present and align with the team to get their buy-in on what they feel comfortable testing vs. implementing based on what the prioritized Airtable is telling us. We align each sprint as business objectives change and plug and play inside the Airtable as we execute our experimentation program.

Danielle Schwolow, Growth Marketing Consultant, Advisor, and Entrepreneur

Keep the Local vs. Global Maxima in Mind

We know that Steph Le Prevost recommends understanding where your website is on the local vs global maxima scale.

Ekaterina Gamsriegler elaborates on why this is important.

The purpose of experimenting is to replace ‘gut feeling,’ and while it is often extremely valuable and can generate a wealth of insights, it can also backfire.

I am referring to the over-reliance on A/B testing, which can hinder innovation. The danger lies in getting stuck optimizing for local maxima instead of striving for the global one. Because the impact of your new solution is only as great as the height of the hill.

Let’s imagine your goal is to increase the conversion rate for purchases, and you believe that optimizing the payment screen can yield big results. However, you have already conducted numerous A/B tests on this paywall and are starting to notice diminishing returns from tweaking it.

You have two choices: continue making incremental changes (adhering to A/B testing best practices) by, let’s say, testing the call-to-action (CTA), then the font size of this CTA, then the rest of the copy, and finally, a slight change to the price. On the other hand, you can also test something different (which may seem random at the beginning), such as a completely different layout of the screen.

If you opt for some version of the latter, it is more likely to be an innovative solution with multiple changes and a higher chance of failing in the A/B test. It might fail simply because it is not yet optimized for the KPIs against which you measure success, and for which the original solution has already been optimized. It requires a leap of faith because while it might fail in the short term, it has the potential to take you to a higher ‘hill’ in the long run.

But how do you measure this potential, and how do you come up with ideas for an innovative solution in the first place?

Just like with many other product-related topics, the answer lies (surprise, surprise) with your users, i.e. qualitative validation.

- When seeking inspiration and ideas to break free from the optimization hamster wheel, do user research. Identify what prevents users from upgrading in the current flow. Is the cancellation policy unclear? Are they concerned about unexpected charges or forgetting to cancel the trial before it expires? Do they find the paid features lacking value? Is the difference between the free and paid versions of the product clear? You can spot a lot of such concerns during user interviews and by analyzing user feedback. Take notes and identify patterns.

- Generate 3+ ideas for the solution and discuss them with your team before committing to one and designing it.

- To evaluate the potential of the innovative solution, involve your users as well. Show them the prototype and observe patterns in their responses.

It is also likely that the innovative solution will impact more KPIs than an ‘optimized’ version of the solution would. So make sure to document not only primary success metrics but also secondary ones, ‘guardrail’ metrics, and potential trade-offs, to properly evaluate its impact.

Ultimately, when planning your experiments, remember about the local maxima and try not to overlook higher ‘hills’ by over-relying on optimization work.

Ekaterina Gamsriegler, Head of Marketing at Mimo

Key Takeaway

We’ve navigated the turbulence of the basic testing program, debunked some myths, and thrown light on the path to innovation. Now, let’s crystalize all the veteran testers’ wisdom into the creation of your balanced portfolio of tests.

First, why did we call it a ‘portfolio of tests’? Picture a wisely chosen collection of varied investments. A rich mix that diversifies risk and aims for the sweet spot of maximum returns.

Your testing program is the same. It should be a diverse, balanced blend of different experiments—each one aiming for a unique business outcome. This balanced approach will be your key to fostering innovation, securing buy-in, validating decisions, optimizing performance, and learning from your audience.

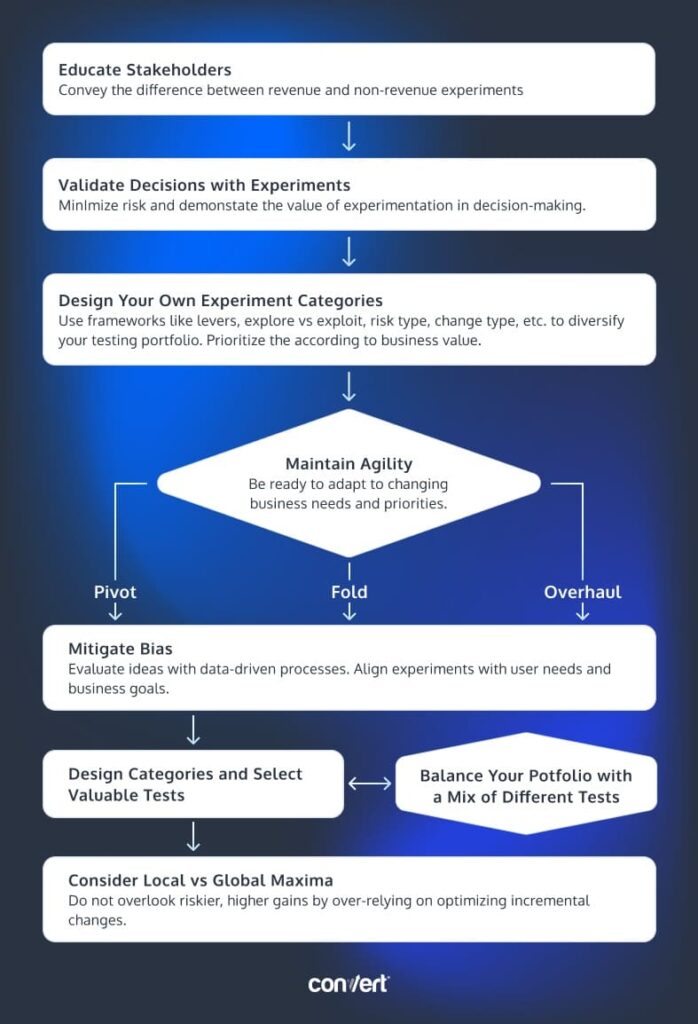

Flowchart is available here:

Step 1: Introduce Stakeholders to Revenue and Non-Revenue Experiments

Educate stakeholders about the distinction and benefits of both revenue and non-revenue experiments, securing necessary resources and setting expectations for both.

Step 2: Validate Business Decisions Through Testing

Leverage experiments to validate decisions like new product launches, minimize risk, and demonstrate the value of experimentation to stakeholders.

Step 3: Design Your Own Experiment Categories

Use frameworks like levers, explore vs. exploit, risk type, change type, etc. to diversify your A/B testing portfolio. Prioritize these tests according to the noticeable value they present to the business.

Step 4: Fold the Lever or the Roadmap!

Maintain agility in your experimentation program. Be ready to pivot, fold levers, or even overhaul the roadmap in response to changing business objectives or non-performing levers.

Step 5: Do Your Best to Avoid Bias

Mitigate bias in your experimentation program by adopting a data-driven process. Evaluate all ideas equally based on research and data, ensuring your experiments align with user needs and preferences.

Step 6: Design Categories and Pick Valuable Tests

Design categories and select valuable tests for your experimentation program, balancing the portfolio and ensuring a mix of different types of tests.

Step 7: Keep the Local vs. Global Maxima in Mind

Keep in mind the difference between local and global maxima when experimenting. Sometimes, you need to be open to riskier, innovative changes to reach the global maxima, learning from failures along the way.

And there you have it! Your complete guide to creating a balanced portfolio of tests. It’s not just about numbers or quick wins; it’s about understanding your users, fostering a culture of learning, and ultimately steering your business toward sustainable success.