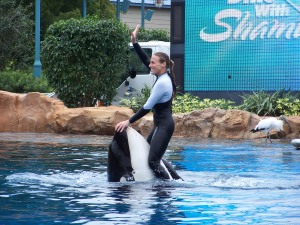

In the first case of its kind, PETA, three marine-mammal experts, and two former orca trainers are filing a lawsuit asking a federal court to declare that “five wild-caught orcas forced to perform at SeaWorld are being held as slaves in violation of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.” The filing—the first ever seeking to apply the 13th Amendment to animals—names the five orcas as plaintiffs and also seeks their release to natural habitats or seaside sanctuaries.

The announcement on the PETA website asks people to “help animals imprisoned by SeaWorld today,” and suggests they to write to The Blackstone Group—the company that owns SeaWorld—to request that “it immediately set in place a firm and rapid plan to release the animals to sanctuaries that can provide them with an appropriate and more natural environment.”

As I prepared to use this high profile law suit as a news hook for a blog post on publicity stunts (although PETA would likely deny the filing is a stunt), I ran across an excellent 2008 post by James L. Horton, entitled “Publicity Stunts. What Are They? Why Do Them?” which is the best explanation and counsel you will find on this topic. Jim Horton is a seasoned PR pro, and a partner at Robert Marston and Associates.

In Horton’s deep dive into publicity stunts, he says “the challenge of any publicity stunt is to preserve the message contained within it.” The acid test, he claim, is that, “Stunts can be elaborate or simple but their importance is the news interest and awareness they generate for the concept/ product/ service being marketed.”

On that basis, PETA’s lawsuit succeeds as a publicity stunt. Off the record, PETA would probably admit that it does not expect the SeaWorld lawsuit to make it to court, much less free the whales. But the massive publicity related to their filing, calling the public’s attention to the rights of animals, is not only consistent with PETA’s underlying mission, but also demonstrates the extent to which PETA is willing to defend those rights.

The flip side of the “Why Do Stunts?” argument is that all this PETA-generated noise may simply drive greater awareness and consumer interest in visiting SeaWorld, which would make Blackstone’s Steve Schwarzman happy. Another unknown involves the extent to which an organization damages its brand by doing something that’s viewed as crazy by the general populace. In this case, has PETA reinforced the notion that they are simply a bunch of “animal nuts,” and diminished its seriousness of purpose?

On that score, PETA decided long ago that having “crazy” associated with its brand is either a risk worth taking, or an attribute it’s seeking.