At Keywee, we’re lucky enough to work with hundreds of the world’s top storytellers. As a way to share some of the lessons they’ve learned with the greater publishing community, we created The Storytellers: an interview series where we speak with some of the most accomplished and forward-thinking leaders from across the industry (including Keywee customers and friends like The Knot, Thrive Global, and Kiplinger).

Below is our conversation with Dan.

––

This interview is going to cover newsletters in detail, so we’d love to start by asking you a question that’s more broad: Why you think email is so powerful?

Email is a channel purpose-built to reach people directly, and over time we’re figuring out how to use it more efficiently. We take it for granted because it’s so ubiquitous. If you were to meet somebody that didn’t have an email address, you would assume that they were from outer space!

I find it amazing just how versatile email is. Email can serve many different needs across an organization. If you’re looking to drive a reader to a story, email can do that. Looking to get a reader to a live event? Email can do that. Trying to turn casual readers of your magazine into paying subscribers? Email can do that, too.

Email is awesome because you can inspire the reader to take a certain type of action: to subscribe, to read, to share. And that has a ton of power in 2019.

Great answer. Now let’s take a step back. Can you tell us about your background in the industry?

I’ve been working in journalism for a decade. I’ve worked at several different news organizations, but most recently I came to The New Yorker as its first Director of Newsletters. Before that I was at BuzzFeed, where I joined as its first Newsletter Editor.

My work is really about building systems for distributing stories — making sure that the great reporting that’s being done is actually getting out to an audience.

We love your monthly newsletter guide, Not a Newsletter. How did that get started?

For the past couple of years I’ve been working with these organizations, launching newsletters, figuring out how to use email to reach and grow an audience. I’ve seen how effective email can be as a tool. I had a lot of experience in the space and had been answering questions from other folks in the industry about how I’d done things. It got to a point where I realized there was a lot there that I wanted to share, so I launched Not a Newsletter back in January.

With Not a Newsletter, I wanted to find a way to get everything that I’ve learned at BuzzFeed and The New Yorker out to a wider audience. Email is an area where people really need help, and they’re looking for advice from voices that they can trust. In addition sharing what I’ve learned, I’m also trying to bring additional voices into the fold. I’d love to elevate some of those voices and make something that’s useful for as many people as possible.

And now you’re moving on to start your own company, Inbox Collective? What was the genesis of that?

Since launching Not a Newsletter, I’ve been fielding questions from readers about newsletter strategy, launching products, paid marketing — the questions run the gamut.

There were so many questions from so many different brands, and I wasn’t sure who to point them towards to help them get the strategy advice they needed. And at some point, I realized: If there isn’t an expert in the industry to answer these questions, then I need to be that person.

That’s what led to Inbox Collective. I’m creating a consultancy that these businesses can tap into to help them solve some of the big questions they have in terms of building their newsletter audiences, engaging those audiences, monetizing their newsletters, and generally doing great work on email.

As BuzzFeed’s first Newsletter Editor, you must have played a major role in the company’s original email strategy. Can you tell us more about that experience?

On my first day at BuzzFeed, I pitched three newsletters. One was a daily newsletter, one was a long-form newsletter, and one was This Week In Cats. People laughed at the third idea, but we eventually launched all three. The daily newsletter was a great product to help us showcase all the different types of work BuzzFeed was doing. Long-form was a new area of growth for us, and the newsletter gave us a way of showcasing those stories. This Week In Cats was geared toward an audience that loved cats, and we wanted to make a fun and silly product for them.

We tried a lot of different newsletters because the BuzzFeed mission was so broad. We had an opportunity to use newsletters to advance a lot of the work the company was doing and build relationships with readers who were interested in all these different parts of what BuzzFeed was great at.

Do you think that the newsletter landscape has changed much since you started at BuzzFeed?

Totally. When I started there was hardly anyone at news organizations who had the job that I did — someone dedicated full-time to working on newsletter strategy, growth, and content. It didn’t really exist. Now, in 2019, it’s unusual to find an organization that doesn’t have people in these roles.

At many brands, there are now entire teams devoted to newsletters, which is really exciting. It’s a huge, huge shift in the landscape. And brands are really starting to get it. They understand how powerful email can be, and are trying to invest in the tools, the technology, and, most of all, the people who can actually make a great email program.

How would you compare your role at The New Yorker to your role at BuzzFeed?

There are two major differences. First, at The New Yorker, we’re supported by paying customers. The New Yorker could not exist without this incredible audience that cares about the brand and pays to support it. So when we acquire a newsletter subscriber, part of our hope is that we can eventually turn that person into such a fan that they are going to subscribe. At BuzzFeed, we were thinking more about the audience growth and traffic. It’s still building brand loyalty, but in a different way.

The other difference is that The New Yorker sits within a larger organization — we’re just one of many brands here at Condé Nast — so we think about how our work is going to impact the other parts of the organization. It’s a very different, yet exciting challenge.

I’ll add, too: Leaving The New Yorker was an incredibly tough decision. But I’m proud of the work we’ve done here, and I’m excited to take the lessons I’ve learned at The New Yorker and BuzzFeed and use them to help more brands get the most out of email.

Let’s switch gears somewhat. You launched more than 40 newsletters between your time at BuzzFeed and The New Yorker. How do you decide what warrants a standalone newsletter?

So there’s a resource I’ve shared in Not a Newsletter, a strategy positioning briefing to help teams walk through what might make a good newsletter.

To start, you have to think about the building blocks that you’re working with to make the newsletter. Is it a personality-driven newsletter? Is it tapping into someone’s identity — who they are, what they care about? Or is it more about providing a particular service? Does it serve a unique need?

You also have to think about how the newsletter you’re introducing would fit in with your larger editorial program.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a newsletter?

My advice to people who are just getting into the newsletter space is always “launch something to learn something.”

I encourage people to test their hypotheses and work to figure out why something did or didn’t work. It’s a continual learning process.

Launching The Royal Baby Newsletter at BuzzFeed, for example, helped us understand that we could launch products around pretty specific verticals and content types. That led us to things like lifestyle newsletters, which led to automated newsletter courses, which later led to courses and products in other languages.

Let’s rewind — did you just say “Royal Baby Newsletter”?

The Royal Baby Newsletter was our first truly unusual newsletter at BuzzFeed. Prince George hadn’t been born yet, but we were writing a lot of content about the soon-to-be royal baby. It felt like, “All right, let’s see what happens if we launch something kind of weird and different — something that’s more of a short-run product.”

Back in 2013, the idea of doing a “pop-up newsletter” about the royal baby was a little out there, but the team was into it and we learned a lot from it. It inspired us to try a lot of other experiments that explored how we could use our on-site content strategy to fuel our newsletter subscriber growth.

What do you think is the best way to drive newsletter sign-ups?

I actually put together this slideshow with 25 different ways to get people to sign up for your newsletter — there are lots of different ways to drive sign-ups. That said, there isn’t one perfect strategy that every single brand should follow.

I still think, personally, there’s nothing that can compare to the power of word-of-mouth referrals and the power building a product so good that people have to tell their friends.

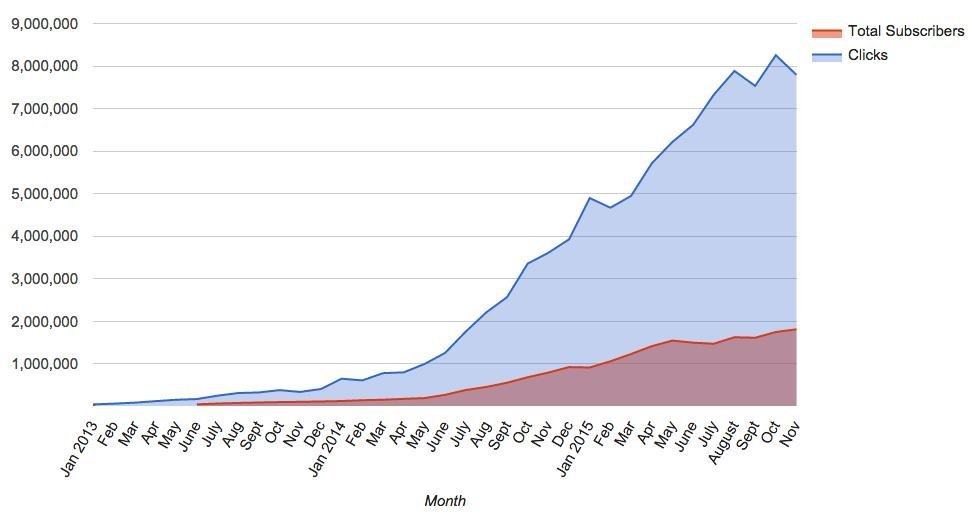

(Buzzfeed newsletter growth during Dan’s first three years with the company.)

Do you have any quick tips for newsletter growth? Any proverbial low-hanging fruit?

I’m going to sound like a broken record on this, but I really mean it:

Continue to think about your subscribers first, and think about how you can engage them in the right way at the right time.

So, for example, pop-up modules can be really useful, but you have to think about who you’re going to show them to and how often you’re going to show them.

Recently, I clicked on an interesting story in a newsletter. It too me to a website that I don’t typically visit, but it was a big U.S. news website. On entry, there was immediately a huge pop-up to sign up to their newsletter. During that session I was shown a total of four pop-ups, and by the time the fourth one happened, I just X’d out. I’d wanted to read the story, but I literally couldn’t.

So, you have to think about the reader first. What is the experience like for them? At BuzzFeed, one of the most effective growth drivers for us were the sign-up modules that existed at the very bottom of the story.

We realized that if you could make it through a list of 37 great cooking tips, then you might be interested in a newsletter that helps you find new recipes.

You’ve said that you view newsletters as a direct relationship with readers or customers. Can you elaborate on that? Why do you think that it’s important to look at newsletters through that lens?

When someone signs up for your newsletter, it’s an opportunity to build a relationship with that person. Not just for today or tomorrow, but for years to come.

You should be asking yourself, “How do I actually establish a relationship and make a connection with these readers?”

With email, there’s an opportunity to think long-term about how you’re going to build that relationship and welcome our subscribers into your world. You have a direct line of communication that’s really powerful. With most other channels you can look a couple of months ahead, but with email you can actually think years out.

At Keywee, we always say that when it comes to growing your newsletter database, quality is just as important as quality. Do you have any thoughts on that?

At the end of the day, email is a personal tool. It’s a tough game to play when you’re thinking about sending emails in bulk — volume isn’t necessarily the name of the game.

Take something like a sweepstakes. Yes, if you’re able to run a successful sweepstakes and sign up ten thousand new subscribers, that’s fantastic. But if you can’t validate those email addresses, or if they don’t like your emails, or they mark you as spam… those can all lead to long-term deliverability problems. Not just for those readers, but for all of your newsletter subscribers.

When you’re launching something big like a sweepstakes that can pull in large numbers of subscribers, you really have to think about how it’s going to affect your list health and long-term deliverability. You should have a plan for how you’re going to validate those email addresses and onboard those readers. If they’re not engaging with your newsletter, then you have to decide how you’re going to try to reactivate them or eventually remove them from your list. That way, in the long run, you’re only retaining the subscribers who are engaged, excited, and want to stick with you for the long haul.

Sometimes the hardest part of writing an email or newsletter is figuring out what the subject line should be. Do you have any notable or funny subject lines that you’ve used?

One time at BuzzFeed we sent a newsletter with “You’re Fired” as the subject line. It was intended to be playful and fun — the email linked to videos of employees screwing up on the job. We sent the newsletter on a Friday morning, and there were BuzzFeed employees on their way to work that didn’t immediately realize that it was a newsletter — they thought BuzzFeed was actually firing them. Needless to say, they didn’t find the subject line very funny.

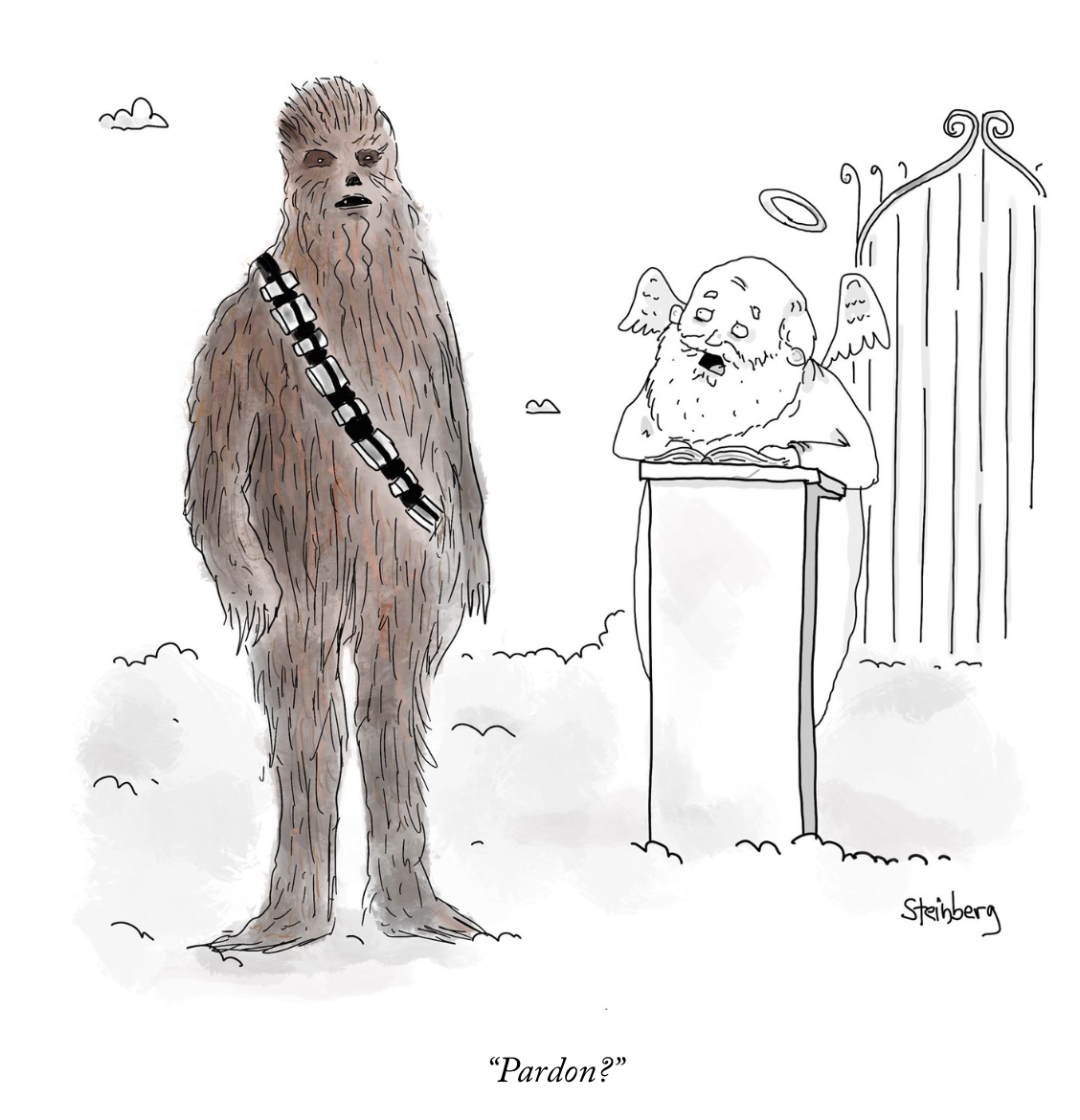

My favorite New Yorker subject line is one we used recently for our Daily Humor newsletter. It was the day after Peter Mayhew, the actor who played Chewbacca, passed away, and our daily cartoon was of Chewbacca at the pearly gates trying to talk his way in and making “Chewbacca sounds.” So our subject line was “Daily Humor: RAWWWGGRRR.” I think a lot of readers opened it because they thought it was a mistake, but they got the joke once they saw the full email.

(Via The New Yorker)

The advice that I usually give to brands is that you have to keep in mind exactly who you are and what you can do. We can be fun in our Daily Humor newsletter, but we would never try something like the Chewbacca subject line for our flagship New Yorker newsletter because it doesn’t suit the tone and voice of the The New Yorker on the whole. At BuzzFeed, though, we could be a little more playful.

Keep in mind that you don’t have to pretend to be fun, either. Don’t add a cat GIF to your email if it’s not appropriate for your brand. Sometimes brands try to push the envelope in ways that don’t work.

Readers are smart — they know when you’re faking it.

What will be your focus for the rest of the year?

I’ll be focused on Inbox Collective. I’ll be working with brands that are trying to figure out how to get the most out of email on all sorts of fronts, ranging from audience development, content strategy, technical issues, and launching new products.

That’s really going to be the focus for the next couple of months. That and working on continuing to make Not a Newsletter the best resource that it can be. Hopefully with Inbox Collective and Not A Newsletter, we’re going to slowly improve the quality of people’s inboxes. You know, one newsletter at a time.

* * *

Thanks so much for taking the time to chat with us, Dan!

__

About Keywee

At Keywee, we make stories relevant and powerful for the world’s best storytellers — like The New York Times, The BBC, National Geographic, Forbes, and Red Bull.

Today, people aren’t coming to websites to search for content — stories find their audiences in feeds and apps. The upshot? Distribution is now the key for effective storytelling. Keywee’s platform unlocks audience insights using AI and data science, and infuses them into every step of the storytelling process: from topic selection, to story creation, to distribution and optimization. Keywee is backed by leading investors such as Google’s Eric Schmidt and The New York Times, and has been a fast-growing, profitable startup since its inception. To learn more, request a demo here.